One of the objectives of writing this blog is to see new things and meet interesting people. This week, I met David Wood (aka Woody), a sculptor who works in metal, primarily hand-forged steel—an artist and high-end blacksmith who makes artistic gates and other metal sculptures.

He invited me to meet him at Bent Metal, his South Melbourne forge and studio. I wrote about one of his public art pieces last year (see my post David Wood in St. Kilda), so I was keen to see more of his work, even if it meant getting slightly lost in the unfamiliar South Melbourne streets. I don’t get across the river often (see my post about Melbourne’s most significant psychogeographical barrier, the Yarra River).

Woods doesn’t look like a blacksmith; he is not some massive muscle man but a guy with a goatee beard and dark-framed glasses, like me. He is a courteous, thoughtful, engaging person with almost no social media presence; he only recently updated his webpage after nearly a decade.

Distances mean that I haven’t seen many of Wood’s public commissions. There are several in St. Kilda, including the five gates to St Kilda Botanical Garden Gates; the others are scattered across the city from Cranbourne to Rye. Woods is equally capable of elegant abstract forms like the two twisting metal planes on Donnybrook Road at Donnybrae and playful, whimsical elements like the cast elements in Hawthorn at the historic Rocket playground. With Wood’s work, metal becomes foliage and the organic mix of sci-fi or fantasy.

Often, they have a practical element that comes from his blacksmithing practice: gates, somewhere to sit like his circle of galvanised steel reeds, Spirit of Place in Elsternwick Park, or the shade of giant metal nardoo leaves, Nardoo Rotunda in Berwick. And then there are the gates, which have both a practical and ritual function as the entranceway of an enclosed area, defining, barring, and opening the space.

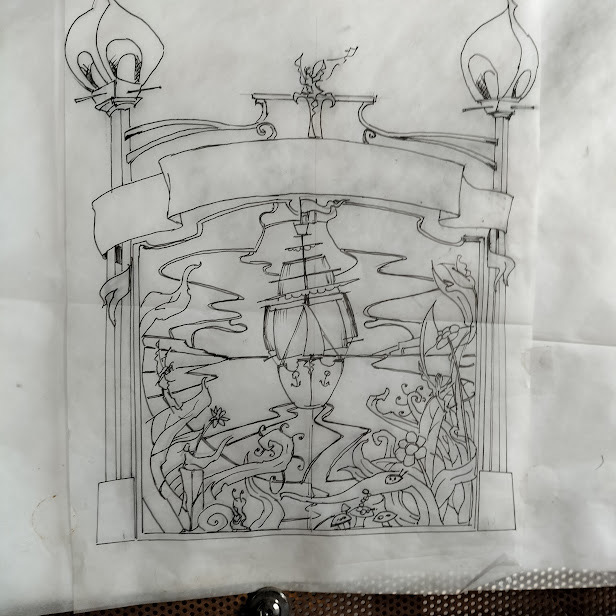

Looking into Wood’s studio, I see a gate with a sailing ship being assembled. Another more classically influenced gate lies on a large table further on. Like all studios, it stores a few sculptures and maquettes (the model for a sculpture) from previous exhibitions. The metal curtains frame a dramatic view, All my Pasts and Futures (2017) People’s Choice Award Montalto Sculpture Prize 2017. Curtains are a kind of visual gate.

His forge is on the ground floor of an old 1890s commercial bakery, the old cast iron oven still built in. His studio is above that. Like many sculptors, Woods has two working areas: an industrial one and an elegant meeting room for clients and doing designs. Both are beautiful work environments with different aesthetics.

Wood’s has the most open artist’s studio I’ve ever seen. The roller doors at the front open onto the street. Random people wonder past, look in, chat about their grandfather’s blacksmith work (Wood’s grandfather was also a blacksmith), and ask if he makes knives (he doesn’t).

We talk and drink tea at a table of recycled wood from the old Newport railway workshop with the wabi-sabi aesthetic of loose screws embedded into the wood. On the table is an old book on Melbourne’s Aboriginal Sites on the table; Wood collects books about Melbourne. Out of the window, we can see the South Melbourne skyline, a mix of light industrial, commercial and residential, now with the residential towers going up. There is a cafe next door on the corner. Do we need biscuits with our tea?

What are your thoughts?