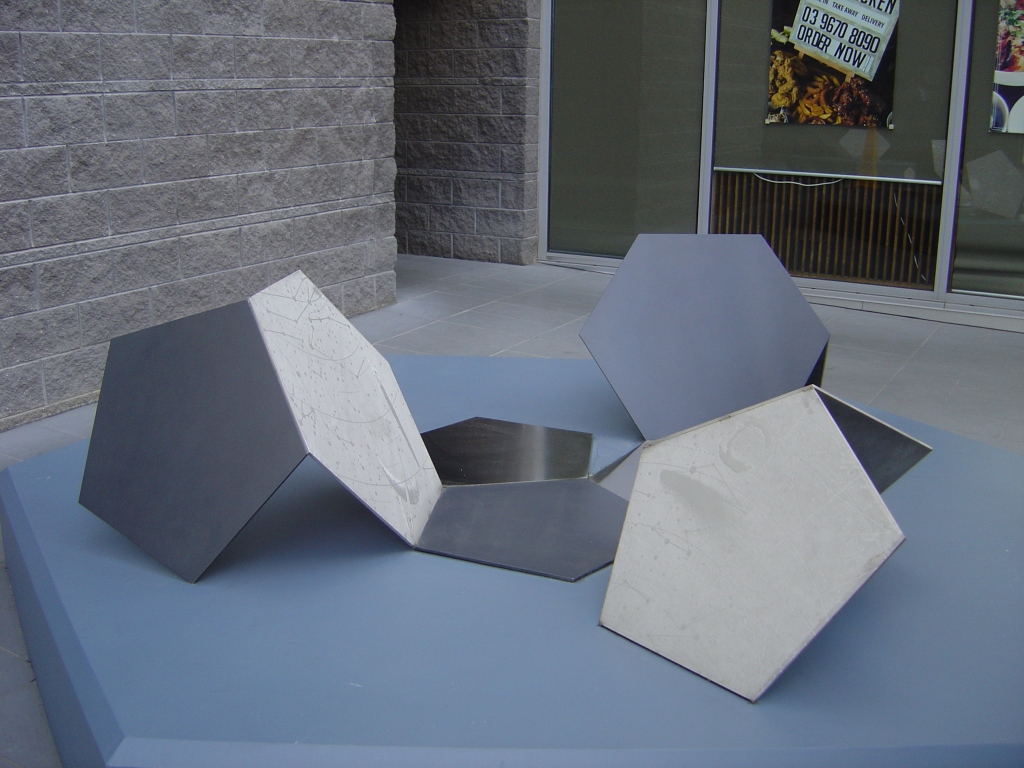

Celestial Ground 2016 by Colleen Boyle is a geometric sculpture about astronomy. Boyle is a Melbourne-based artist fascinated with outer space (I must have seen one of her exhibitions over the years as she has exhibited in galleries I regularly visit, like the Counihan Gallery, Blindside and First Site).

The sculpture forms a constellation of its own in front of a building in the Docklands with low plinths, information panels along the wall and extending into the footpath. The folded metal plates are etched with images of the southern night sky and mirror polished plates, reflecting like a telescope. The pentangles and hexagonal steel plates and their low hexagonal concrete plinths painted Payne’s grey reference a type of carbon (C60) found in space. The plinths are also the right height for seats so you can get comfortably close to the images of the constellations.

Commissioned by Wonderment Walk Victoria in collaboration with RMIT University and Victoria Point. (What is Victoria Point apart from a residential suburb southeast of Brisbane? Perhaps it is the building’s name.) This is the second sculpture I have seen commissioned by Wonderment Walk Victoria; see my post on John Olsen’s Frog sculpture.

Boyle and Olsen are not primarily sculptors. Why does Wonderment Walk choose artists who are not primarily sculptors? Wonderment Walks commissions public sculptures and installations that combine science, mathematics and art. This certainly includes Boyle and some of the other sculptors, but that concept gets stretched to the meaningless to include portraits by Vincent Fantauzzo and kitsch sculptures by Gillie and Marc. It seems in many cases star power is more important than science, but not for Celestial Ground.

Celestial Ground is not the only piece of public art in Melbourne with references to the stars. Another is World Within, World Without (2010) by Helen Bodycomb, a mosaic on the south bank of the Yarra depicting the time at which former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made his national apology to the ‘Forgotten Australians’ represented by the constellations above Victoria at 11 a.m. on 16 November 2009.